If you’ve invested in a foam filled fender, the last thing you want to see is water getting inside. These fenders are designed to stay buoyant and reliable even in tough marine environments, but if water starts seeping into the foam core, performance can drop fast. So, what actually happens if water gets in? Is it dangerous? Can you fix it, or do you have to replace the whole thing?

Let’s break it all down step by step.

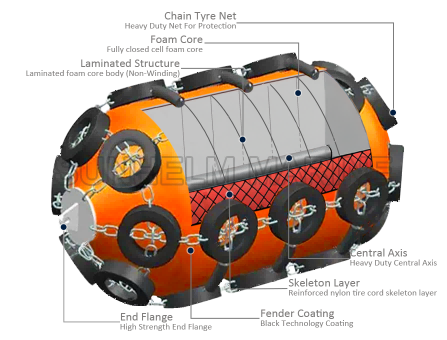

How Foam Filled Fenders Are Built

Before we talk about water ingress, let’s quickly understand what’s inside a foam filled fender.

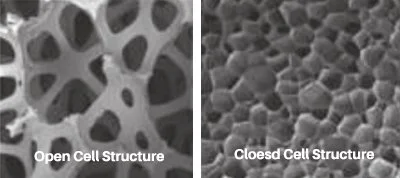

- Closed-cell EVA or PE foam core → Provides high buoyancy and naturally resists water absorption.

- Tough polyurethane (PU) outer skin → Protects against impacts, abrasion, and UV damage.

- Reinforcement layers → Usually nylon or fiberglass to add strength.

- End fittings and hardware → Flanges, swivel eyes, and optional chain/tire nets.

This combination makes foam filled fenders durable and low-maintenance, but they’re not indestructible. If the skin gets punctured or the hardware loosens, water can find its way in.

When Water Gets Inside: What It Means for Your Fender

Here’s the thing: the foam itself is closed-cell, so it doesn’t soak up water like a sponge. That’s good news. But if the polyurethane skin is compromised, you can end up with free water trapped inside cavities. Over time, this causes several issues:

1. Reduced Buoyancy

If your fender starts to float lower than it used to, that’s a clear red flag. Water pockets inside the fender make it heavier, and less of it stays above the waterline. For vessels, this means:

- Less clearance between the ship and the quay

- Higher chances of hull-to-hull or hull-to-dock contact

- Ineffective energy absorption during berthing

2. Compromised Energy Absorption

A foam filled fender works by compressing its foam core to absorb kinetic energy. When water fills internal cavities, parts of the fender can become “dead zones” that don’t compress properly. You’ll notice:

- Hard spots where the fender feels stiff and unresponsive

- Uneven load distribution during impact

- Increased reaction forces transferred directly to the hull or dock

3. Accelerated Internal Damage

Trapped water, especially seawater, brings its own set of problems:

- Saltwater accelerates corrosion on end fittings and inner reinforcements

- Freeze–thaw cycles can expand cracks inside the foam

- Marine growth often clusters around damaged areas, worsening abrasion

In short, once water finds a way in, the problem tends to snowball if not addressed quickly.

Why It’s a Safety Risk

A compromised foam filled fender isn’t just less effective — it can become unsafe in high-stakes situations like STS transfers, LNG terminals, and offshore platforms.

- Unexpected slippage: Less buoyancy means the fender can sit too low, allowing direct hull-to-hull contact.

- Overloaded hardware: Extra weight puts more stress on chains, tire nets, and end fittings.

- Operational downtime: Damaged fenders may need to be pulled from service, delaying berthing schedules and costing money.

If your fender is part of a safety-critical setup, water ingress isn’t something you can ignore.

How to Decide: Repair, Refurbish, or Replace

Not every case of water ingress means you need a new fender. Here’s a simple decision guide:

| Damage Level | Symptoms | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Minor surface damage | Small cuts, no buoyancy loss | Clean, patch, monitor |

| Moderate ingress | 5–10% buoyancy loss, small soft spots | Remove, repair, re-skin |

| Severe damage | >15% buoyancy loss, multiple punctures, core collapse | Full refurbishment or replace |

Key Factors to Consider

- Age of the fender → If it’s already 8–10 years old, replacement is usually more cost-effective.

- Duty cycle → High-pressure operations like VLCC or LNG berthing demand full performance.

- Downtime costs → Sometimes a quick swap beats waiting for refurbishment.

Repair Solutions: How It’s Done

If the damage is manageable, there are several repair approaches:

1. Field Patching (Small Cuts)

- Clean and dry the area thoroughly

- Sand the edges to improve adhesion

- Apply a primer and polyurethane elastomer patch

- Allow full curing before reuse

This is fast and effective if the core hasn’t been compromised.

2. Localized Plug and Re-Skin (Moderate Damage)

- Cut away the damaged outer skin

- Remove any degraded foam

- Insert a new closed-cell foam plug

- Seal and re-skin with PU coating

This restores buoyancy and structural integrity without replacing the whole unit.

3. Full Refurbishment (Severe Damage)

- Remove the entire outer skin

- Replace the foam core

- Overhaul end fittings and nets

- Re-skin and re-certify the fender

This is the most expensive option but extends the service life almost as much as a brand-new unit.

What Not to Do

Never drill “drain holes” to remove trapped water.

It sounds tempting, but it actually accelerates damage, lets more water in, and voids warranties.

Preventing Water Ingress in the First Place

Here’s how to make sure you don’t end up dealing with this headache again:

- Right sizing matters → Don’t overload a foam filled fender by using one that’s too small for your vessels.

- Protect the skin → Install chain/tire nets or chafe pads to prevent sharp-edge damage.

- Regular inspections → Check for cracks, soft spots, and freeboard loss at least quarterly.

- UV protection → Re-coat or treat polyurethane skins in high-sunlight regions.

- Proper handling → Avoid dragging fenders on rough surfaces or dropping them during lifting.

A little preventative maintenance goes a long way toward extending the life of your fender.

FAQ

Will my foam filled fender sink if it takes on water?

Not immediately — the closed-cell foam will still float even with some water ingress. But severe flooding can reduce buoyancy enough to make the fender unsafe.

How much water is “too much”?

If you notice more than a 5–10% drop in freeboard or the fender feels significantly heavier, it’s time for inspection and likely repair.

Can I keep using a fender while waiting for repairs?

Maybe, but only for low-risk operations. For high-energy berthing or STS transfers, damaged fenders should be pulled from service.

Can I DIY the repair?

Small surface scratches, yes. Anything involving internal foam or structural integrity should be handled by specialists.

Conclusion

A foam filled fender is designed to perform reliably even in harsh conditions, but water ingress can compromise its buoyancy, energy absorption, and safety. The good news? If you act early, most cases can be repaired without replacing the entire fender.

Stay proactive: inspect regularly, patch small issues quickly, and choose refurbishment or replacement when performance is at stake. With the right maintenance, your foam filled fenders can last for many years without letting you down.